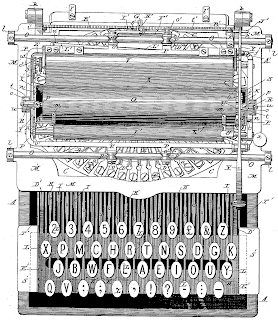

Mrs L. V. Longley's Typewriter Lessons were not sufficient to carry the day immediately for the proponents of eight-finger typing. She was denounced repeatedly in the pages of Cosmopolitan Shorthander and eventually was challenged to prove her case by another teacher of typewriting from her own city. The challenger, one Louis Taub, proclaimed the superiority of four-finger typing on the Caligraph. This was a rival machine which had been brought out in 1881 by Densmore's former partner, Yost. It came equipped with a six-row keyboard, accommodating upper- and lower-case keys to make up for its lack of the Remington's shift-action. In 1888, when the first public speed-typing competition was organized which put to the test these contending systems, the honor of Mrs Longley and the Remington was vindicated by a Federal Court stenographer from Salt Lake City who had taught himself to type on a Remington No. 1, way back in 1878. Frank E. McGurrin, the man who entered the lists as their champion against Louis Taub, already had won fame in demonstrations before gasping audiences throughout the West, because, in addition to deploying the `all-finger' technique, he had memorized the QWERTY keyboard. -- Paul A. David: "Understanding the Economics of QWERTY: the Necessity of History", Economic History and the Modern Economist (William N. Parker ed., Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1986), pp.30-49.

Scrutinizing the Cosmopolitan Shorthander, from June/1884 to February/1889 issues, I could find only one article that denounced eight-finger typing (cf. "Typewriting Instruction", The Cosmopolitan Shorthander, Vol.8, No.5 (May 1887), p.113) but no other. Denounced repeatedly? No. Several articles recommended use of the ring finger and sometimes the little finger. If Prof. David really read the Cosmopolitan Shorthander, he would never mistake the competitor's name, Mr. Louis Traub, for Taub, and would never argue that Mr. Frank Edward McGurrin vindicated Mrs. Elizabeth Margaret Vater Longley.

In 1888 Mr. Louis Traub was a principal of Longley's Shorthand and Typewriting Institute, Cincinnati (cf. "The Challenge Accepted", The Cosmopolitan Shorthander, Vol.9, No.6 (June 1888), p.155). He had been an eight-finger typist on Caligraph No.2 since Mrs. Longley moved to Los Angeles in May, 1885 (cf. "Elias Longley's Farewell", The Cosmopolitan Shorthander, Vol.6, No.11 (November 1885), p.200). Mr. Traub did not challenge Mrs. Longley, but he vindicated her eight-finger method. Mr. Frank Edward McGurrin was an official stenographer of the Third District Court in Salt Lake City, not of the Federal Court there (cf. "The Question Settled", The Cosmopolitan Shorthander, Vol.9, No.8 (September 1888), pp.226-227). He was an all-finger typist on Remington No.2 and could operate it blindfolded (cf. "The Metropolitan Stenographers' Association Typewriter Contest", The Cosmopolitan Shorthander, Vol.9, No.8 (September 1888), pp.217-218). Mr. McGurrin did not vindicate Mrs. Longley, but he was challenged by one of her pupils. On July 25, 1888, Mr. McGurrin won the typewriter competition in Cincinnati against Mr. Traub. After the competition, Mr. Traub threw his Caligraph away, and started to practice with Remington (cf. "McGurrin vs. Traub", The Cosmopolitan Shorthander, Vol.10, No.2 (February 1889), pp.21-23).

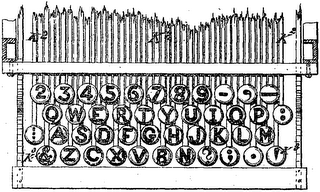

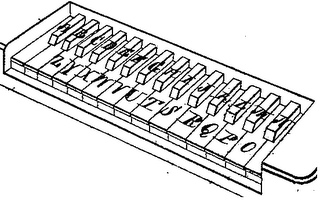

Mr. Christopher Latham Sholes' first type-writing machine, whose patent was filed on October 11, 1867, had a two-row keyboard, neither single-row nor piano-like (shown right, taken from

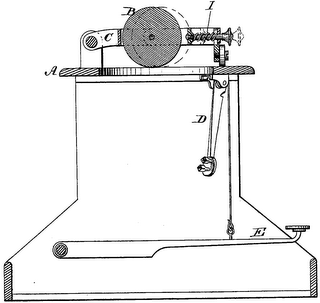

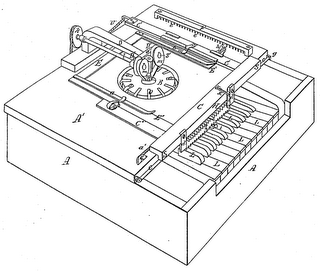

Mr. Christopher Latham Sholes' first type-writing machine, whose patent was filed on October 11, 1867, had a two-row keyboard, neither single-row nor piano-like (shown right, taken from  and then imitated piano-like keyboard of the Hughes-Phelps printing telegraph (shown right, taken from

and then imitated piano-like keyboard of the Hughes-Phelps printing telegraph (shown right, taken from